Why I wrote historical play 'Afonja' - Playwright, Sakky Jojo

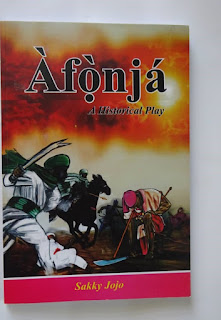

Saka Aliyu PhD, (Sakky Jojo), published his first play Afonja in the year 2018. He had published a Prose earlier (Altine) in 2003 and he is into Poetry as well. We took him up with questions relating to his current work –Afonja- a historical play. First his biography, his goal of writing, the controversy surrounding the dramatic narrative of the play, the canons and the unique approach to them and the attention Afonja received in terms of performance and its use as a pedagogical drama text in tertiary institutions. Enjoy the interview:

UJ: Can we know who the playwright is?

SJ: My name is Saka Aliyu, as I like to be simply referred to. Sakky Jojo is the pen name I have been using since my undergraduate days at Usman Dan Fodiyo University, Sokoto. I grew up in Ilorin where I was born and thereafter in Sokoto. I trained as a historian, with a terminal degree from Leiden University. I worked briefly in Benin, then Kaduna before joining Bayero University in 2008 as a lecturer.

UJ: What is the goal of writing Afonja?

SJ: There were some goals of writing that play. One, it is history of my hometown and which I feel very much connected to. The story is a good recipe for playwriting, particularly the tragedy that it is. Secondly, I felt that being a controversial story, I need to bring out the story in proper perspective. I feel by doing so, I am doing some peace building. For when a story is given in its proper perspective, it will help dissipate controversies for those who care to know the truth. Two, the history of Ilorin with the rest of the Yoruba speaking nation can be controversial because of the contexts in which they occurred and interests and the misunderstanding that comes out of that. Personally I don’t like controversies, for in the end it reeks of ignorance and half-truths. But then controversies are part of the gears that moves the world.

|

| Dr. Saka Aliyu |

SJ: Variety, they say, is the spice of life. I was being innovative stylistically there. I was used to the ‘acts’ and ‘scenes’ myself. Then I noticed some playwrights using ‘movements’ and I was intrigued. I thought what a way not be cliché. So when I started writing Afonja, in the final round, I decided why not use something different and I thought ‘context’ is most apt. All scenes are contexts. It is just style and my little contribution to the lexicon of drama.

UJ: Some people believe that the Afonja story is controversial, what can you say to that?

SJ: It is indeed and one of the aims of writing the play is to chip at the edges of these controversies through story telling in historical perspectives. As someone whose history and identity is connected to that story, I felt the need to put the story in their proper contexts for clearer understanding. What you read in the media are often ‘history in a hurry.’ These are often sensationalized. The stories are deeper and more connected and complicated than can be easily grasped on the surface. At the heart of this controversy is Yoruba irredenta that from time to time tugs at the cloak of Ilorin as a politico-cultural entity. For me, as I said earlier, this play is also a peace building effort, hoping it will bring more understanding and less controversy.

UJ: How do you feel as a historian reconstructing history through literature?

SJ: It is a double honour for me. I found myself connected to two things, history and literature, both using story-telling as means of expression and finding expression in each other. While history attempts to reconstruct the past, especially the past of man as far as memory in its various forms can afford, literature tries to reflect the life of man as much as its mirrors can reflect. Unlike history, literature has leeways. It can twist in ways history cannot do. Literature can afford to be magical. Literature can augment history, which is what I have done in the play.

UJ: In your attempt at writing drama, why “historical Play” is it that you feel more comfortable as a historian?

SJ: Apart from the patriotic instinct, it just happened to be the first play that came to my mind. I think I am comfortable with other forms of drama. I have written satires, comedies and adaptations too. Afonja just happened to be my first full length play. I don’t know if I will do other historical plays but for now, I think I have made my contribution in this area.

UJ: Afonja has received attention and has been performed in places as far as Ilorin, Ibadan, Gusau, Kano and several other places. Why the popularity?

SJ: I think the play was particularly propitious. It has done well beyond my expectation given that I did very little in terms of publicity. It was first staged in Ibadan by students of God’s Blessing Comprehensive High School, Yemetu, whose teacher bought a copy. They were most splendid and ambitious. Unfortunately I could not attend the performance due to my busy schedule. A friend represented me and he was most impressed as well. I feel I owe the school a great deal for the honour done to me. I had sent some copies to Ibadan for sale and it was from those copies that one was bought and used to stage the play.

Then students of the Department of Performing Arts, University of Ilorin, also staged it and it was used in one of their courses. That, I owe to Professor Rasheed Adeoye who happened to be my mentor and technical guide in my first attempt at playwriting. It was studied at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and Federal College of Education, Zaria and in my own university, Bayero University, Kano, where we now have a growing Theatre and Performing Arts Department as well as in the Department of English and Literary Studies. It is out of print now and I hope to reprint as soon as I can afford to.

My only regret is that it has not been critically engaged as much I would love to see. Perhaps, that is because I have not written the play as a controversy to favor or discredit one side against the other. Humans generally love controversy and one of my aims is to show that the controversies around the subject matter are largely out of context. With all modesty, you will need to be widely read to critically engage with the play. What I brought to bear on the play is the whole of my lived experience. It had taken me 18 years to finally finish the play and get it published and it was fifteen years since I published any work.

UJ: Can we say Afonja is an instance of Art in the service of history?

SJ: Yes, very much so and vice versa!

UJ: Is Afonja as reflected in your book a tragic hero and what manner of tragedy is explored in the play?

SJ: Afonja is indeed a tragic hero, in the Hegelian sense as I have written in the preface.

UJ: You talk of ‘poetic license’ in the preface to the play Afonja which you noted has been given wings throughout the play can you expatiate that further for the readers to get a clear picture.

SJ: Poetic license is the stuff of literature. It is the opportunity you have to spice up a story, to exaggerate or underplay, twist or even change storyline even for a historical story. It is the embellishments that make any story interesting. It is like the embroidery of literature that adds colour and beauty to the basic elements in the story. Since even for the historical events being reconstructed we do not have the minute details, we use imagination; say to put words, actions and even attires on the characters in believable ways. You will see stories within story, proverbs, and cultural norms in the play. I particularly used parameology (proverbs), made allusions to Yoruba medicinal practice, coded communications, incantatory and initiatic practice, Islamic jurisprudence and the multiculturalism that has been part of the Ilorin milieu since the era in which the play was set. You will see the play spiced up with four languages apart from English in which it is written.

UJ: What was it like writing the play?

SJ: I enjoyed writing the play, though it had taken me longer than it should. But that has its blessings. In the years it was in limbo I had gotten two additional degrees and thus sharpened my intellect and worldview. I started in 2001, then an unemployed graduate. Then I had to get my masters, did some social work, got employed as civil servant, then as an academic and then getting a terminal degree. Finally I decided I just have to break the jinx of not having a work published in almost two decades. That was the push that did it. I thought it a shame being called a writer and not having a major work out in one and half decade. We’ve got only so much time in this world.

UJ: How do you combine your writing with being an academic?

SJ: When I sent a copy to a friend at Oxford, who is also an academic, she had asked ‘how did you do it with all the workload?’ It was then that it occurred to me that indeed it was not easy. Since I published it I have been trying to edit a poetry anthology and still unable to finish it, now in its third year. So it is really not easy, one need some grace.

UJ: What are the plans for the future?

SJ: I hope to find time to publish my other works and perhaps write others. I consider myself as a prose person but I have not done much in that area to my satisfaction. I hope to go back to it. Playwriting is very technical but somehow I find it easy to write. I think poetry is everywhere and a lot of people are writing it. I see myself as an accidental poet. If there is an award for ‘unfinished works’ I think I deserve that award. I hope to dust my old works, polish them and get them out there. Time is not on anybody’s side.

********

Umar Jibril, the Interviewer, is a writer, previewer and literary essayist based in Gusau. Apart from his day-job as Ombudsman at Public Complaints Commission, Abuja, he earns a living as part-time MD of Educraft Consulting, a knowledge platform based at Gusau and Kaduna. He could be reached via ujibril85@gmail.com

Comments

Post a Comment

We love to hear from you, share your comment/views. Thanks